A herb-like plant found in abundance along North America’s West Coast which is known as the western false asphodel has been known to science since 1879. But it is only recently that researchers from the University of British Columbia discovered the innocent-looking plant’s penchant for insects. The finding is particularly exciting given that this is the first new predatory plant to be discovered in 20 years.

“We had no idea it was carnivorous,” says study co-author and botanist Sean Graham. “This was not found in some exotic tropical location, but really right on our doorstep in Vancouver. You could literally walk out from Vancouver to this field site.”

The researchers stumbled upon the plant’s well-kept secret accidentally. While studying plant genetics, they noticed that the western false asphodel lacked the same gene as other insect-munching plants. Since the plant thrives in the same kind of wet, sunny habitat with nutrient-poor soil as other carnivorous plants, they wondered if it trapped bugs for nourishment as well.

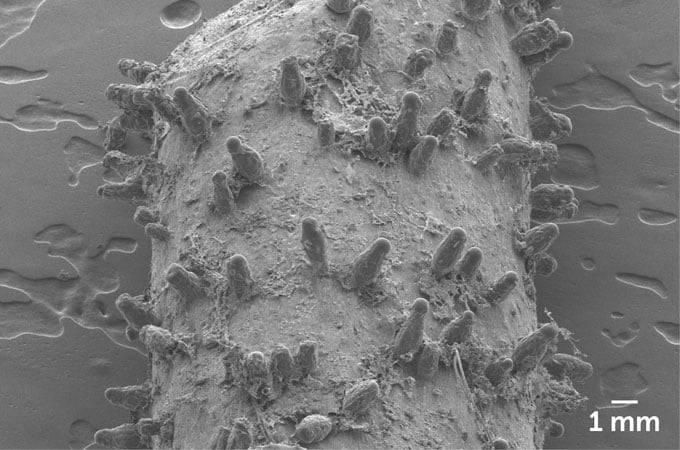

“And then they have these sticky stems,” Graham told NPR. “So, you know, it was kind of like, hmm, I wonder if this could be a sign that this might be carnivorous.”

To test if the plant could absorb animal nutrients, the team attached some dead fruit flies to the stem’s sticky hairs. The insects had been fed nitrogen-15 isotopes. The commonly used technique allows scientists to determine the flow of the gas. Sure enough, they found that over half of the wildflower’s nitrogen came from the fruit flies. Additionally, the digestive enzyme released by the plant’s sticky hairs to break down the prey was similar to that found in other carnivorous plants.

The scientists, who published their findings in the August 17, 2021, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, say this is the first time they have encountered predatory traps on the flower’s stem. Most carnivorous plants develop unique structures further away from their flowers to prevent accidentally killing pollinators. The western false asphodel can get away with its unusual prey-capturing technique because the sticky hairs on its stem can only capture small insects such as midges, not the larger bees or butterflies involved in pollination.

This unexpected scientific finding raises the possibility of finding many other carnivorous plants hiding in plain sight. “It’s a good reminder that we still don’t know much about the ecology of a lot of individual plant species, even in well-known environments, ” says study co-author Dr. Qianshi Lin.